Appliance Types and Policy Goals

B. Catalytic and Non-catalytic Wood Stoves

The modern stove emerged in the early 1990s after Oregon State established emissions and testing requirements, which were then adopted by the EPA as national requirements. Emissions can be further reduced using catalytic combustors, like those used in vehicles, which work as smoke afterburners, or using non-catalytic systems. The original EPA certification program had two phases of implementation several years apart, with gradually tightened emissions regulations, giving the industry some time to adjust to the more strict standards. The Phase II EPA certification, still in effect today, required non-catalytic wood stoves to emit less than 7.5 grams of particulate matter per hour (g/hr) and catalytic wood stoves to emit less than 4.5 g/hr. The EPA Phase II generation of wood stoves is typically 7-15 times cleaner than older models, 40%-50% more efficient and typically uses 30-40% less wood. Naturally, these improvements save homeowners work and money. The EPA is currently in the process of developing a New Source Performance Standard (NSPS), which early discussions indicate will recommend non-catalytic wood stoves to be 4.5 g/hr or under and catalytic wood stoves to be 2.5 g/hr or under.

Figure 28: Non-Catalytic Wood Stove (EPA)

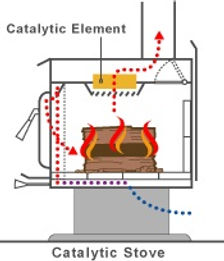

Figure 29: Catalytic Wood Stove (EPA)

Generally, non-catalytic stoves are the less expensive option and most range in price from $800 - $3,500, but as their combustion is less complete than catalytic stoves, they tend to burn through wood more quickly. Catalytic stoves have longer burn times and use wood more efficiently than most non-catalytic wood stoves, but are often on the higher end of the price range. They also tend to burn cleaner at lower burn rates than other stove models, which is an important characteristic since many stove owners operate their appliances at low temperatures when the weather is milder. Because of this, catalysts are well suited for situations when a long low burn is desired or for whole home heating needs since the firebox on catalytic stoves tends to be larger than non-catalytic stoves (which tend towards smaller, hotter fireboxes designed to decrease particulate emissions).

Though the catalyst does contribute to a cleaner burn, the drawback of older catalytic stoves is that when the catalyst is damaged or wears out, the stove then burns less cleanly than advertised. New catalytic stoves have greatly improved the durability of the catalyst and now should perform as consistently as non-catalytic stoves (both types of stoves may degrade for different reasons over time). For a more in-depth discussion of the pros and cons of catalytic and non-catalytic stoves, please click here.

For some, there remains the perception that catalysts are inherently short-lived. This was the case in the early nineties when many wood stove companies raced to meet the new EPA standards by adding poorly designed catalytic converters to stoves not equipped to utilize them. However, those models have now been taken out of production due to their fallibility, and the catalysts on the market today are well designed and long lasting, provided that dry, untreated wood is burned. An OMNI laboratory study showed that the average increase in emissions was less than 1 g/hr over nine years.